There are rare instances in the realm of motorcycle design when there emerges an icon. These are machines so radical that they serve as a clean break from the standards of the past, thereby setting a new template and pushing the high-water mark up the wall a few extra feet. To truly be an icon, they must influence subsequent processes and inspire a new thread in motorcycle design; one-off machines that immediately fade into obscurity won’t do.

They can be new standards of beauty, or of performance, or of chassis design, or templates for hitherto untried categories (or some combination of all four). These motorcycles are often the product of years of research and countless design hours, produced by multi-billion dollar corporations that can afford to take a risk once and a rare while. They are not often produced by a tiny boutique manufacturer that has built less than a thousand machines, conceptualized by men who were not classically trained “designers” with decades of experience under their belts.

The Confederate Wraith was one such icon of that emerged from Southern Louisiana like a thundering slap in the face to all that the motorcycle industry held dear. It was an absolute break with tradition, a bold insult to the long-held standards of a conservative industry, and a new way of conceiving of the motorcycle that was unlike anything that had preceded it. It was a product of looking forward while respecting history, a curious mixture of old and new ideas blended into a stunning machine that was as brutal as it was intelligent.

The story of the Wraith must begin, inevitably, with the story of Confederate. Founded in 1991 by H. Matthew Chambers, Confederate was as much a product of Chambers’ ideology and uncompromising principles as it was the result of a desire to introduce a new concept in American motorcycle manufacturing. A long time motorcyclist and passionate student of Southern history, Chambers was far from the prototypical entrepreneur.

After a series of career changes he earned a law degree and practiced as a trial lawyer in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. He established a successful practice and earned a tidy income, but dreamed of contributing something greater to the world. After winning a particularly grievous personal injury case in 1990 and earning a considerable fee, he sold his share of the practice to his partner and with a million dollars of his own money set out to start his dream project: an American motorcycle that would eschew the stagnant design and commercialization of the American market in favour of an heirloom-quality machine that would have dominating performance.

His plan would spark the renewal of an industry that had not existed in the Southern United States since Simplex had faded into history. In conception and execution it would prove to be a labour of love born of high-minded ideals and a desire to renew craftsmanship in an industry that had become driven by profit margin.

Chambers’ ideas were as esoteric as they were inspiring, a lone voice in the wilderness calling for a conceptual shift in the way motorcycles were designed and built in America. Design and construction would be unhindered by considerations of profits. Individualism would be emphasized, as would mechanical detail and craftsmanship. Nothing ancillary or unnecessary would be present. The machines would be raw and would command respect from their riders, channelling their uncompromised nature through their performance. Chambers’ tenets called for a renewal of what he called “The American Way” and the abandonment of “The American System”: at its core the idea is to bring back quality, pride and craftsmanship in American manufacturing instead of promoting materialism, stagnant design, and marketing falsehoods. This rhetoric continues to inspire confusion among the masses who have been weaned on cheap mass-produced motorcycles fluffed up with contrived links to a mythos cooked up in the boardrooms of multi-billion dollar corporations.

The name Confederate, often a source of controversy in the early years of the company, was a product of Chambers’ appreciation of Southern history and his unapologetic bucking of convention.

Much to the chagrin of politically-correct followers and “Yankee” interviewers Chambers celebrated the exploits of Southern heroes, citing them as the inspiration for the company’s rebellious spirit. Racial implications were never a part of the program but were often brought up by media members who focussed on the negative aspects of Chambers’ heroes, rather than accepting the philosophical implication of his celebration of the South and a pure spirit of rebellion against an overwhelming adversary.

In Chambers’ idealized view the South was railing against the Northern corruption of American ideals brought on by the imposition of centralized government, a parallel to how Confederate was fighting the stagnation and materialism that had enveloped the motorcycle industry. He pointed to the lack of industrial development in the South as a result of the history that followed the Civil War, a situation he aimed to correct by promoting manufacturing in the region. In recent years this rhetoric has been softened somewhat in Confederate’s marketing material, but the basic principles still linger.

Chambers approached drag-racing specialist Kosman Specialties in California to develop a chassis for his motorcycle. A stiff, well-engineered frame would be needed to ensure the good handling that most American motorcycles seemed to lack. While ideas for a chassis using a unitized engine as a stressed member were fielded, in the end the choice of a non-unit Harley-pattern big twin for motivation led to the development of a steel cradle frame with a massive three-inch backbone. A two-inch front downtube doubled as the oil tank for the dry sump engine. A triangulated rear swingarm operated a straight-rate rear suspension supported by a pair of shocks operating on a single pivot, ala HRD Vincent. Ceriani forks supported the front, with twin Performance Machine rotors and calipers providing meaningful stopping power. A five-speed gearbox developed in conjunction with Kosman and Sputhe rotated the gear shafts 90 degrees, then flipped the countershaft to the right side of the bike, to create a vertically-stacked transmission that aided packaging and created a structure stiff enough to support the swingarm pivot - an innovation that would become a Confederate signature.

The first prototype hit the road in 1994. Dubbed the Grey Ghost, this machine set the basic template of subsequent Confederates – a long, low chassis with top quality suspension and brakes, with minimal bodywork surrounding a hulking “radial” twin, Confederate’s term for the 45-degree layout that references the history of the V-twin as a slice-of-a-radial-engine arrangement. Power for the first machine came from a 93 cubic inch (1525cc) S&S-produced big-twin clone; production machines would use a variety of powerplants from S&S and Merch, and specifications varied considerably over the course of production.

Customers could customize most elements of their Confederates, and chose from a variety of engine, suspension, wheel, and brake combinations - an American cruiser with 17-inch Marchesini wheels, fully floating Brembo cast iron rotors, and adjustable WP forks? While these first generation machines might seem relatively conventional by our current standards, what with the proliferation of factory “customs” and “muscle” cruisers in recent years, but in the mid-1990s there truly was nothing like a Confederate on the road. It was the prototypical brutish sport cruiser, a distinctly American machine that could go, turn, and stop, while looking mighty badass in the process.

Production of customer motorcycles began in Baton Rouge in 1996, later moving production to Abita Springs, with prices starting in the high $20,000 USD range, easily clearing $30,000 if you checked signed off on a few of the options. The machines bore names that drew inspiration from American history; the Hellcat, standard bearer of the Confederate line, was named after the Grumman F6F Hellcat that served as one of the United States Navy’s most successful carrier-based fighter aircraft in the Pacific Theatre of the Second World War. The emblem on the hand-built fuel tanks bore the inscription that served as the company letterhead and the final throwdown to anyone who might have missed the Southern Cross engravings on some of the components: “Confederate Motors, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Sovereign, C.S.A.”

Like many American motorcyclists who desired something that would challenge The Motor Company’s hegemony of the market, JT Nesbitt was smitten by the Hellcat. While working as a freelance journalist for Iron Horse, during the magazine’s golden years under Editor David Snow’s leadership, Nesbitt had the opportunity to ride a Hellcat Roadster for two days in Daytona Beach, Florida. At the time the magazine was a bastion for the sort of honest, irreverent, and intellectual writing that has long been absent from the mainstream motorcycle press, making it a favourite for misfits and writers with actual opinions who desired more freedom than any meddling advertiser would allow. Iron Horse in the mid 1990s was a gold mine for creativity and honesty, and helped kindle the legitimate do-it-yourself chopper culture that has since been bastardized by the hipster set.

Nesbitt had briefly met with Matt Chambers in 1995 and again in 1997 prior to testing the Hellcat, a series of encounters that would signal the beginning of a partnership that would end up redefining what constituted the American motorcycle.

At the time Nesbitt was freelancing as a writer while waiting tables, a bachelor’s degree in Fine Art under his belt. Nesbitt had dabbled in motorcycles as part of his sculptural projects and had a keen interest in their design and construction, but was not trained in industrial design through the traditional avenues – a background that would prove to be an asset.

The original Confederate went bankrupt in 2000 and closed the Abita Springs factory after producing between 300 and 500 machines, depending on who you ask. Chambers regrouped and restarted the company in New Orleans in 2001, and it was around this time that Nesbitt reached out to Chambers to ask for a job. Chambers agreed and Nesbitt began his tenure with Confederate by hitting a home run in the redesign of the Hellcat dubbed the G2.

The G2, also called the F113/F124, served as a template for Confederate’s subsequent design language. While the G1 Hellcat had been a relatively conventional-looking machine supported by high-quality components and excellent attention to detail, the G2 was a mean, vicious son of a bitch that soon drew the attention of the public and the motorcycle industry, making Confederate the darling of celebrities and well-heeled riders looking for the ultimate in performance and exclusivity. The big twin and cradle frame were still present, as was the Confederate vertical gearbox, but all the details were reworked into a package that was completely unlike any other production machine on the market.

Everything that wasn’t billet aluminum or titanium was made of carbon fibre, including the fuel tank. The G2 was ugly in the best possible way, elemental and a bit rough with no extraneous baubles distracting from the purpose of going fucking fast. It looked “purposeful”, if we can forgive a hackneyed motojournalist cliché.

Nesbitt devised a way of using the swingarm as the exhaust, by way of a triple-layer Inconel bellows connecting the headers to the curved, hollow swingarm tube. Thus far the G2 Hellcat is the only motorcycle design to route the exhaust in this manner; the Riedel Imme R100 used the exhaust pipe as a swinging arm, but the powerplant was rigidly attached to the arm/pipe and moved in tandem with the rear wheel. Twin Penske shocks supported the rear.

Adjustable 50mm Marzocchi forks and six-piston radial mounted brakes up front suggested a sporting machine, but a 240mm width rear tire and a carbon-fibre tractor saddle said something else before being drowned out by the fury of a too-much-is-just-enough 124 cubic inch S&S mill which thumped out 130hp and arm-wrenching 140 lb/ft torque at the rear wheel.

These massive engines and obscene power figures proved to be more than enough to fling the 530 LB brute down the road with the sort of immediacy and drama that made motojournalists wax poetic about the capabilities of what was supposedly an “antiquated” 45-degree twin - when they weren’t busy pointing out the astonishing $60,000-plus price tag, anyway. It performed like it looked – brutal, uncompromising, and awe-inspiring.

After years of operating in relative obscurity, Confederate and Nesbitt were suddenly on the radar with a design that had made them the bad boys of the boutique/custom motorcycle world. While other builders were busy hacking together damn-near unrideable, chrome-addled, over-commercialized odes to the chopper scene, Nesbitt had perfected a new breed of machine that created a new category overnight.

The new aesthetic was not flawless chrome and airbrush paint jobs tarting up ridiculous machines with absurd chassis geometry: it was the intelligent application of functional, mechanical art that respected heritage without being a slave to tradition. It was raw materials arranged around a taut core, a big-ass motor barely contained within a modern chassis supported by the best components and no frivolous parts distracting from the singular purpose of the machine. It had a few subtle nods to bygone designs, but applied in a way that didn’t look like anything but a vision of the future. In a way the G2 Hellcat was a self-fulfilling prophecy, leading to countless imitators and more than a few Confederate wannabes who emerged to fill the newly discovered market for a modern but distinctly American custom.

But the G2 wasn’t what Nesbitt truly desired to create. Despite the genre-defying elements and radical styling, the Hellcat was still a relatively conventional motorcycle: engine in the middle surrounded by a steel cradle frame, telescopic forks up front, and a swinging arm at the back. It wasn’t that far removed from the G1 in terms of chassis design despite the marked difference in styling.

Nesbitt had been mulling over a new conception of the motorcycle that would represent a break from previous design language. At its core, his idea is to reverse the accepted order of the machine: build the bike around the engine. While it sounds like an obvious statement, it isn’t the way motorcycles have been conceived in the past.

The basic structure of a motorcycle is a bicycle with an engine clipped on – a motor added to an existing chassis. Most supposedly modern motorcycles aren’t far removed from that original formula; pull the powerplant out and remove the bodywork and the rolling chassis of a lot of machines still look like an overgrown bicycle with fancy suspensions bits. The engine almost seems like an afterthought, bolted into place wherever it will fit. Nesbitt’s idea was to start from zero and design the entire motorcycle around the engine in an effort to create a coherent whole.

The genesis of the project began as a conversation between Nesbitt and Chambers on a long cross-country drive just as the G2 was being readied for production. Nesbitt had his own peculiar formula laid out, what he called “circles and lines”.

To summarize Nesbitt’s idea in the simplest, most unjust fashion: the engine and wheels are the circles, and the horizontal planes connecting them together are the lines. The 45-degree twin favoured by Confederate worked well as a slice of a pie, a fraction of a radial engine, whose form Nesbitt would complete by closing the imaginary circle around the engine with a chassis and suspension of his own devising.

These ideas were first fleshed out with endless sketches and a scale model, progressing in late 2003 when Nesbitt built a full-sized (but non-running) concept around a Harley-Davidson XR750 powerplant. The machine was utterly alien in appearance. A rolled aluminum backbone served as the frame, with the rear shock mounted inside the spine at the rear supporting a single-sided swingarm.

A multilink girder fork with carbon-fibre blades, inspired by the Britten V1000, was suspended by a coilover shock set in parallel with the steering head. A simple leather saddle was perched on the frame with no subframe, the old-world seating contrasted by narrow sporting clip-ons on the front end. There were hints of stripped down board track racers and, by Nesbitt’s own admission, Italian racing bicycles. The result was an radical mixture of old and new elements applied in a completely distinct fashion that referenced the past without attempting to recreate it.

Bodywork was limited to a scoop-shaped bellypan wrapped around the sump of the engine and tightly-fitted fenders on the wheels. The engine took centre stage, exposed and menacing within the otherwise graceful curves of the chassis, fed by a pair of open carburettors and vented through a shapely heat-wrapped two-into-one header.

It looked like an elemental, stripped down motherfucker of a machine, little more than a motor with a seat attached. As Nesbitt intended, the engine dictated the design in spectacular fashion.

Despite being nothing more than a visual experiment that was patched together from parts bin leftovers and Bondo, Nesbitt’s creation caused an immediate sensation in the motorcycle industry. Featured on the cover of the premiere issue of Robb Report Motorcycling in Spring 2004, the newly-christened “Wraith”.

The machine was named after the Scottish colloquialism for ghost, described by Chambers as “a name derived to echo man’s notional denial of and rebellion against death”, while Nesbitt elaborated “A wraith is a willowy image of your future dead self coming back from the hoary netherworld to portend your imminent doom.”

The concept sparked a flood of inquiries from parties interested in this creation that had been cobbled together in the back of the Confederate factory.

In December 2004 the jury of the Motorcycle Design Association of France awarded the Wraith second place in that year’s Concept Bike Category. Despite the interest there were no immediate plans to put the Wraith into production, or even produce a functional prototype. Nesbitt and Chambers didn’t even know how to put the design into production, as the chassis had not been developed beyond what was effectively a three-dimensional sketch.

In light of the success and innovation of his designs, Nesbitt and Confederate Creative Director Grant Ray were invited to make a presentation at the 2004 Industrial Designers Society of America Eastern conference in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Nesbitt and Ray took to the stage in front of a group of design students, accompanied by a bottle of Maker’s Mark. While Nesbitt was wheeling a G2 Hellcat into the room in front of the crowd, a man in the audience whispered to him: “start the bike.”

Nesbitt paused, then obliged, sending a thundering racket throughout the building and enthralling the audience by unleashing all the fury of his creation in an enclosed hotel conference room. With their appropriate introduction completed, Nesbitt and Ray proceeded to get properly drunk during the presentation. They showcased the G2 and shared Confederate’s modus operandi, finishing up by informing the bright-eyed students they “had wonderful futures flipping burgers at McDonalds”. In the closing minutes of the slideshow they flashed images of the Wraith mockup on the screen, hinting at the possibility of a future design in spite of Chamber’s insistence that production wasn’t feasible.

Confederate’s spirit of rebellion was flaunted in dramatic fashion, with a degree of honesty and reckless bravado that made a significant impression on many present. The man who had encouraged Nesbitt to light up the G2 against all considerations of fire codes was one of them. His name was Brian Case, a local industrial designer who ran Foraxis Design Solutions in Pittsburgh, and this was his introduction to Confederate. He vaguely recalled the relatively conventional machines the company had produced in the 1990s, and was absolutely floored by the design of this new generation of machines that Nesbitt had conjured up.

Case desperately wanted to know more about who was behind this new machine that was so unlike anything else. The images of the Wraith shared during the presentation left a deep impression on him, and he wanted to be a part of the project. He approached the duo after the presentation and called them “true rebels”. He gave Nesbitt his business card, telling him he would be happy to offer his skills in CAD design to help put the Wraith into production.

Nesbitt added the card to the pile that he had amassed from eager audience members following the presentation. It might have been forgotten among the dozens of other offers to join the Rebellion, had it not been for a chance encounter later that night.

Case was invited through a friend to join a penthouse party following the IDSA conference. He arrived to find the room packed and everyone well and truly drunk. After some mingling he bumped into Nesbitt and Ray and began chatting with them, in the traditional way motorcycle guys tend to gravitate together and swap war stories no matter what the venue may be.

After some time Nesbitt addressed the elephant in the room. “What the fuck happened to your hand?” Case lamented that he had mangled his left hand in a CNC mill accident, and the resulting surgeries had left him with a fused finger. He hadn’t been able to ride a motorcycle for the past four years due to the injury, as it prevented him from operating the clutch lever. Nesbitt had a simple solution: “Dude, you've got to cut that thing off.”

Two weeks later Case had his left ring finger amputated. Ecstatic at the prospect of riding once again, he called Nesbitt just to inform him that he had done the deed. Nesbitt immediately asked him if he would like to work for Confederate.

Case was a skilled designer in his own right and particularly adept at Solidworks and CAD modelling, a skill set that would serve the company well in subsequent years. But there were still no plans to put the Wraith into production, and Chambers was adamant that the project was not feasible.

Nesbitt formulated a plan. On a Friday afternoon, one week after Case had called him, he loaded a 100ci S&S Super Stock Sportster-clone engine from the company shop in New Orleans into a van and drove to Pittsburgh without Chamber’s knowledge. In Pittsburgh Nesbitt met with Case to sit down for a beer and cigarette -fueled marathon session to finalize the chassis design of the Wraith around the engine Nesbitt had “borrowed”.

When Chambers discovered that his designer, the S&S mill, and the company van were missing, he contacted Nesbitt. He informed Chambers that he could fire him, but in four days he would return and re-apply for his position. When he returned from Pittsburgh he presented a series of CAD files detailing a monocoque chassis that he and Case had developed for the Wraith. Chambers was so impressed with the progress the pair had made in such a short period of time, and the innovation of their solution for a strong but easy-to-manufacture frame, that he greenlit the project and allowed development to continue - after re-hiring Nesbitt.

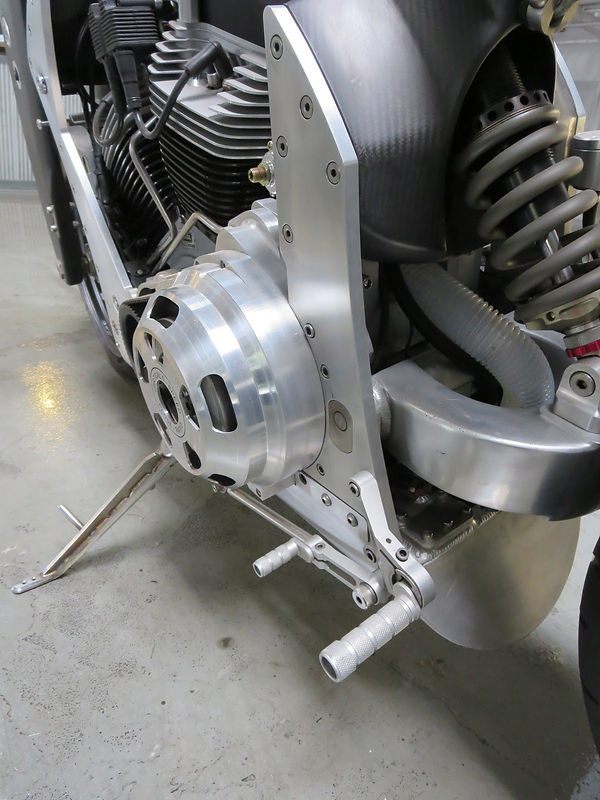

Nesbitt and Cases’ solution was to use a U-shaped formed aluminum shell that wrapped around the bottom of the engine, which was held together with fore and aft bulkheads that were fastened with shoulder bolts that penetrated through the shell and served as locating pins into the bulkhead – positively locking the skin into the bulkheads.

This featherweight 14 pound carbon-fibre backbone would double as an oil tank for the dry-sump engine. Wings moulded into each end of the backbone would be bolted to the shell, which cradled the 1640cc motor as a stressed member. This monocoque “fuselage” (folded around the engine “like a taco” as Nesbitt likes to put it) required a unit construction Sportster clone – while the Sportster has a separate transmission and external primary case like a traditional Harley big twin, it is held in unit with the engine crankcases by a casing that allows the power unit to be used as a stressed member.

This marked a significant departure for Confederate, who had hitherto relied on big-twin powerplants mated to their proprietary gearbox design, which necessitated a traditional (albeit strong) steel cradle frame.

The chassis was remarkably simple despite its radical appearance. All that would be required to manufacture the monocoque skin would be a flat sheet of aluminum, cut to shape with countersunk holes drilled for the mounting points, folded into the final shape by a hydraulic press.

One piece, no welding, no jigs - the result would be a strong and extremely light frame that would allow the Wraith to be produced with a relatively quick turnaround by the tiny manufacturer. Fuel would be carried in a cell hidden in the hollow space below the sump of the engine, at the base of the “taco”, lowering the centre of gravity and eliminating the need for an unsightly tank up above. The exhaust collector would also be placed within the taco, fed by a pair of wrapped header pipes that snaked around the cylinders into the cavity below - this in the days before heat wrap became de rigeur for any hack builder trying to dress up their XS650. Two ports cut into the left side of the shell served as the exits.

Mass centralization and simplicity was the aim, but the resulting appearance was that of the bastard lovechild of a piston-engine fighter aircraft and a board tracker. It looked impossibly badass, compact and tightly packaged, stripped down to only the barest functional elements wrapped around a massive engine.

The rear suspension would be relatively conventional, with a straight-rate monoshock mounted within the hollow backbone acting on a single-sided swingarm. The front end was what really set the Wraith apart. The basic girder layout presented on the concept machine would be refined with milled alloy rocker links and an adjustable coilover shock mounted ahead of the steering head, but would retain the carbon-fibre fork blades. It looked wild at first glance but was quite simple in execution, with far fewer components than a telescopic fork.

Girder designs are nothing new, though they are quite uncommon in modern designs: the technology has existed for a century, debuting as the Druid fork, a solid fork supported by a spring on a parallelogram linkage, introduced in the 1910s. In the early days of motorcycling when suspensions of any sort were in their infancy girder designs of various configurations were favoured for their strength and stable geometry, and their ability to separate braking and steering forces from the suspension action. Hydraulically-damped girder forks became a signature of Vincent twins, which used Brampton items before developing their own forged-blade Girdraulic design in the late 1940s as a more rigid alternative to the era’s highly flexible telescopic forks.

Nesbitt and Case set about building a running prototype, dubbed the XP-1, in mid-2004. Early on Nesbitt expressed a desire to field the completed machine at the speed trials on the Bonneville Salt Flats, scheduled a scant four months later. At the time Confederate didn't have the resources to participate in the trials.

To ensure that his creation would get a proper baptism at the Flats Nesbitt “resigned” from the company while continuing to work on the XP-1, asking Chambers to withhold his salary so the company could afford to run the machine at Bonneville. Case also worked without pay during this period, abandoning his Pittsburgh studio to work in New Orleans - completing the Wraith would be a labour of love for both of them, and both men paid expenses out of their own pockets to see it through. Seeing their passion for the project, Chambers relented and agreed to take the completed machine to the Flats.

XP-1 was completed in time to be entered into the first annual BUB Speed Trials in August, 2004. Confederate electrician Chris Roberts volunteered to ride the prototype across the salt, rising to the challenge in a stunning moment of bravery. Roberts, who had hand built the electrical system on the XP-1 (as well as all production Confederates), was a man with no experience at Bonneville who was expected to ride a priceless (and unproven) contraption, put together in a few months by a pair of iconoclastic designers, as fast as he possible could across the Flats.

Testing had been limited to a few blasts along the Interstate near the Confederate factory before loading the machine into the van and heading for Utah. To add to the pressure XP-1 was earmarked for delivery as soon as the trials were over. XP-1 became known as the McKenna bike, destined to be installed as a piece of sculpture in the home of a prominent California automobile dealer owner after it had proven itself at Bonneville.

The trial was ultimately successful, but not without drama.

After several days of rain, the Flats were slicked with a thin layer of water and runs had to be delayed while the surface dried. The salt remained damp when XP-1 was scheduled to run, reducing the top speed and adding to the challenge. Bonneville’s surface is notoriously slippery even in the dry, as you might expect when you are driving a high-powered vehicle across a bed of powdery, abrasive material at ludicrous speed.

As per FIM and AMA regulations all competitors must complete a two-way pass through the course to earn their official time, their final speed calculated from the average of these two runs through the markers. Roberts and the XP-1, entry number 99, were on the course at the same time as a streamliner with entry number 999. Roberts had finished his first run and was waiting to begin his second pass in the other direction. Meanwhile 999 was waiting to begin its run at the opposite end of the course.

When the call was made for 99 to complete its second pass through the markers, the driver of 999 misunderstood and took off – on a collision course with Roberts. Disaster was averted but the incident nearly had the upstarts from Confederate ejected from the trials. Video proof was presented to show that the call was made for 99 and it was the streamliner driver was at fault, not Roberts.

Roberts ran over 139 MPH across the salt and the crew shared a moment of triumph before delivering the bike to its new owner. The Confederate legacy had been established at the Flats, and all subsequent machines produced by the company would be fielded at Bonneville as a test of their performance and the company’s resolve in producing the fastest American production motorcycles. Nesbitt returned to the National IDSA conference with Case and Chambers where they showcased the results of the Wraith endeavour and screened a video of XP-1 running at Bonneville.

With XP-1 delivered to its new owner, work began on a pre-production prototype that refined the chassis design and prepared the Wraith for (limited) series production. While outwardly similar to the McKenna bike, aside from the liberal application of black hard anodizing, a number of notable improvements were implemented in what would become known as the Black Bike. Changes were made in the hopes of creating a more streetable (but still awe inspiring) machine - something more suitable for public consumption than the XP-1, which had been built with Bonneville in mind.

The monocoque, carbon fibre backbone, and Sportster-pattern engine would remain, but the front suspension was reworked. Instead of a coilover shock mounted ahead of the steering head, Nesbitt envisioned a spring enclosed within the steering neck, damped with a cartridge contained in a cavity filled with hydraulic fluid. It was essentially a rearranging of the internals of a telescopic fork applied in a unique way, with the suspension centred along the steering axis. The spring would be connected to the forks by a pullrod mounted to a rising-rate linkage, pulling down from the bottom of the steering head to compress the spring via a plunger cap mounted above.

While the XP-1 had used a highly-tuned 100ci Super Stock engine, the Black Bike used a more “docile” 101.6x92.1mm 91ci (1490cc) powerplant built for Confederate by Revolution Performance. Fitted with two massive 48mm Super G carburettors, a reversed rear cylinder head, and Confederate’s signature vertically stacked six-speed transmission, this was not your typical Sportster mill. Power was a claimed 125hp at a screaming 7400 rpm with 104 lb/ft of torque – at the rear wheel. Semi-wet weight, without fuel, was 425lbs.

Performance from this combination of light weight and massive torque was impressive, but the chassis also shined. Wheelbase was 58.5 inches with a rake of 27 degrees, fitted with 17 inch wheels that could accommodate sportbike-sized rubber – no slow-turning 240 rear ala Hellcat here, instead the Wraith used a 5.5 inch width Marchesini forged alloy rear wheel shod with 180mm Metzeler rubber. Traxxion Dynamics supplied the suspension units, a modified Penske shock at the rear and a custom damper for the unique front end.

Alan Cathcart was given the opportunity to ride the Black Bike in an early state of completion in 2005. His impressions were favourable, noting a very compliant ride and excellent handling. His only gripes were the odd seating position and the lack of a tank to grip with your knees when cornering (the white hot rear cylinder serving as a poor substitute), and some fueling issues from the Revolution engine that were addressed, but not fully sorted, during his test. Remarkably, the Black Bike was assembled shortly before Cathcart rode it and was not complete finished. Though he did not reveal the fact in the review the front suspension did not have any damping mechanism installed, making the tidy handling all the more impressive and serving as a testament to the stability of Nesbitt’s fork design.

Development of the Wraith continued, with production anticipated to begin in the Fall of 2005. A target retail price of $47,500 (later revised to $55,000) was proposed – making it considerably less expensive than the existing Hellcat and reflecting the simplicity of the chassis’ production. A release party for the first production Wraith was scheduled for Halloween eve, with a procession of bikes meeting at the Confederate factory before touring the warehouse district of New Orleans.

In late August Chambers and Nesbitt were invited to the Middle East to discuss a business arrangement with an undisclosed funder somewhere near the Persian Gulf, described as a prominent figure who was an existing Confederate customer and enthusiastic supporter of the company.

Plans were made to pay the debts of the company and fund the construction of three new models without compromising the American ownership of the company. A deal was struck and Chambers and Nesbitt spent the night celebrating before retiring early on the morning of August 28th. Upon their return to their private residence they tuned into CNN and watched in horror as reports were broadcast of a category four hurricane making its way straight for New Orleans. The epic high of their salvation at the hands of a wealthy patron was immediately crushed by the realization that their friends, family and business were now at the mercy of the wrath of God and nature, and they could do nothing but watch from the sidelines on the other side of the world.

Hurricane Katrina made landfall in Louisiana on August 29th. Chambers approached his backer and offered to annul the deal in light of the possibility that the factory might be destroyed. The backer refused to go back on his word and assured Chambers and Nesbitt that the agreement would stand no matter what the outcome of the storm.

Katrina would prove to be one of the single most destructive storms in United States history, and one of the deadliest hurricanes on record. In addition to the destruction wrought by the hurricane winds, New Orleans was devastated when the levee system failed and flood waters blanketed 80% of the city. Nesbitt returned to Louisiana and established his parent’s home in Shreveport as a safe haven for the company employees and families, all of whom were fortunate to have survived the nightmare that Katrina and its aftermath had wrought upon the city.

Some preparations had been made at the Confederate factory in anticipation of possible flooding, but nothing prepared the employees for what they would encounter when they returned to the site. The West wall and the roof had collapsed, and the building that had served as the company’s factory and headquarters since 2001 was completely destroyed. The Black Bike had been on exhibition in New York at the time and was spared, eventually finding a permanent home in the Trump Tower, but the heart of Confederate was in ruins. Some frames and most of the company files were recovered but it was clear that that Confederate as it had been was no more, and another complete renewal of the company would be needed.

Chambers made the decision to relocate the factory to a new location, a move that led to a great deal of turmoil for Nesbitt. Nesbitt remained fiercely loyal to the city he loved and refused to leave, thereby parting ways with Chambers and Confederate. Nesbitt had promoted a sincere desire to inspire a renewable and sustainable industry in the region, an industry driven by skilled labour that would manufacture commodities for export in a place which had hitherto relied on cultural exports and oil money to keep the coffers filled. It was a philosophy that had endeared him to Confederate and Chamber’s desire for a renewed industrial presence in the South.

These ideals would drive Nesbitt to found Bienville Studios alongside Dave Hargreaves, another refugee from the Confederate Family, where he would continue his own peculiar brand of uncompromising industrial design in the heart of the French Quarter.

Meanwhile at the renewed Confederate Motor Company Brian Case and Nesbitt’s protégé, Edward Jacobs, were tasked with taking over the Wraith project. After a period of canvassing for locations and favourable economic conditions, the decision was made to move the company to a new facility in downtown Birmingham, Alabama. Under Case and Jacob’s direction the Wraith would be reborn along with Confederate, taking on a form that was distinct from Nesbitt’s original vision but no less iconoclastic in its execution.

Nesbitt speaks with Chris Roberts at Bonneville in 2004. Roberts, who worked for Confederate until 2006, was murdered at his New Orleans home in 2007 while trying to stop a robbery.

It is late 2005 and Confederate Motors is in shambles. Fresh from the epic high of securing a high-profile investor in the Middle East, the company’s president Matt Chambers and lead designer JT Nesbitt returned to their New Orleans base of operations to discover that their factory has been destroyed by the winds and flooding brought on by Hurricane Katrina. With their facilities in ruins and their insurance company bankrupted by the claims in the aftermath of the storm, it looks like the infamous purveyor of brutal, radical and rebellious motorcycles is no more. Katrina has seemingly crushed the hopes of bringing Nesbitt’s iconoclastic Wraith design to production.

The situation appeared dire and the circumstances were debilitating, particularly for a tiny boutique manufacturer that had constantly fought with debt, flirted with bankruptcy, and struggled to meet the demand for their two-wheeled anti-establishment icons. A few frames and components were salvaged from the ruined factory, as were most of the computer files and company books, but the operation was a long way away from building bikes - particularly when New Orleans was still wracked with instability, crime and resource shortages in the wake of flooding. In spite of the literal collapse of their New Orleans factory, Confederate’s anonymous investor/saviour had maintained his end of the agreement and would provide the capital needed to renew the company.

The question remained: with the factory gone and New Orleans in shambles, where would Confederate build its bikes?

The unstable period following Katrina led to a great deal of internal turmoil and emotional conflicts within the company. Former employees of Confederate often liken their time at the company as being part of a “family”, a tight-knit and sometimes conflicted group of misfits who loved each other as much as they believed in the machines they were helping create. Many suffered long hours and paltry (or nonexistent) wages to help support the company in times of financial trouble, their contributions a true labour of love that spoke to the passion they felt for what they were building and the charismatic nature of the philosophy that Chambers espoused.

It was not a surprise, then, that following the horror of Katrina and the destruction of the factory many intense emotions would come to fore. The period following the hurricane is rife with conflicting stories, disagreements, and defensive statements that need not be repeated here. All that is important for the telling of this story was that the ultimate outcome was that Chambers made a decision to leave New Orleans and start the company anew in a more favourable location, and JT Nesbitt made the decision to leave the company and remain in Louisiana.

Brian Case continued to work as a consultant for Confederate through his Pittsburgh-based company, Foraxis. In addition to helping Nesbitt design and build the Wraith XP1 and B91 prototypes, Case had a team of CAD modellers working on digitizing the components and blueprints for the G2 Hellcat into ThinkId files to streamline production. Following Katrina it seemed that Foraxis would lose its biggest and highest profile client, but Chambers saw a place for Case in the post-Katrina re-organization of the company and began discussing the possibility of bringing him on board.

It would prove to be a difficult but momentous moment in Cases’ career – here was the possibility of leaving his stable business to join one of the most innovative and adventurous motorcycle companies in the world. Case felt that there was nothing else that could be as fulfilling as working for Confederate. It seemed like a dream opportunity, and in spite of the destruction wrought by Katrina there appeared to be promising opportunities on the horizon.

After canvassing locations across the United States an offer was extended for Chambers to visit Birmingham, Alabama in December 2005. The offer was made by local magnate and motorcycling icon George Barber. A wealthy industrialist who had made his fortune in the dairy industry and local real estate, Barber was renowned for building the finest collection of motorcycles in the world: the world-class Barber Vintage Motorsports Museum is home to largest and most thorough catalogue of rare, significant, and historically important production and racing motorcycles anywhere in the world.

George Barber is an imposing but well respected figure in the Birmingham area, a powerhouse business maven who balances his acumen with a friendly, cordial attitude that has earned him a great deal of respect in the local community. So when George Barber makes you an offer, you pay attention. Chambers was invited to the Barber Motorsports Park to discuss the possibility of moving to Birmingham, and made a point to bring Case along. Barber made a strong case for the move with some significant incentives, including a year's free rent in an 8,500 square foot downtown warehouse on Fifth Avenue South to get the operation back on its feet. An agreement was made and after several months of insecurity Confederate was set to move to Birmingham.

Tentative plans were made to build a 25,000 square foot state-of-the-art production facility adjoined to the Barber Vintage Motorsports Museum two years after Confederate relocated, with production facilities and offices being setup at the downtown location in the interim. The partnership between Barber, Confederate and the city of Birmingham became big news in the local media, with an official announcement made at the museum and a high-profile photo op that saw Alabama governor Bob Riley riding a G2 Hellcat around the Motorsport Park track. Much ado was made about the economic benefits that the company could offer the region, with jobs for as many as 250 employees and tens of millions of dollars of investment going into the local economy. Chambers announced an intention to build 150 machines in 2006, with double that expected in 2007, ultimately reaching a target of a lofty 900 examples in 2008.

Confederate seemed to be a part of a series of economic windfalls that were benefiting the Birmingham area, an explosion in growth and culture that was spearheaded by a gentrification of the industrial areas of the city’s core. Confederate was among dozens of trendy businesses, restaurants and breweries that were popping up in the city and spurring on the growth of some interesting progressive cultural development within the region.

Press releases made it seem like Confederate was part of some hipster gentrification movement, the motorcycle manufacturer to the stars - conveniently located across the street from an independent theatre venue. The media oversimplified the purveyors of the Art of Rebellion into a cute boutique/craft manufacturer making curious-looking bikes for wealthy clients. It was in line with Chambers’ ideals of promoting uncompromising design and craftsmanship, and the construction of “heirloom quality” machines... But it marked a noticeable softening of the abrasive damn-the-North ideology that inspired Chambers to adorn his G1 Hellcats with a decal that stated the Confederate States of America as their place of origin and to name one of his motorcycles after Nathan Bedford Forrest.

Once plans were made to relocate to Birmingham, Chambers made Case a formal offer to join the company with the ultimate goal of finishing development of the Wraith. His colleague Ed Jacobs would be tasked with the proposed Renovatio project, a radical machine that would represent the rebirth of the company (but would, unfortunately, never reach production). Case left his partner in charge of Foraxis and moved to Birmingham to become Confederate’s head of operations. Enthusiastic about the prospect of helping resurrect the company, Case also hoped to fulfil a personal promise he had made to Nesbitt several months prior – he intended to see the Wraith project through to completion and put Nesbitt's design into production, albeit in a form that would be quite distinct from the two prototype machines.

Case, Chambers and Jacobs were the first and only employees of the new Confederate. The immediate goal was to resume production of the G2 Hellcat as soon as possible, and for the first six months Case coordinated vendor relations and supply chain management. What few parts were salvaged from the New Orleans factory were put to use in the new series of machines, including the first Hellcat produced after Katrina - built for Ryan Reynolds, who had placed his order before the hurricane. Chris Roberts soon joined the company once again to continue his work as Confederate’s electrical engineer.

With production of the Hellcat underway, Chambers asked Case to continue on the Wraith project. A chance phone call from an unlikely champion helped give impetus to the project. One day Case happened to answer the phone when Eddie Van Halen called to inquire about a motorcycle he had seen featured in a two-page spread in a certain lifestyle magazine. That machine was the B91 Wraith - the Black Bike that was now in private hands, the property of a wealthy enthusiast who kept it displayed in the living room of his Trump Tower apartment. As a youth growing up in the 1980s Case had idolized Van Halen, and made a promise to Eddie that he would build him a Wraith. Van Halen, attempting to reassure Case that he was indeed THE Van Halen, sent him a surreal email – several photos to prove who he was, accompanied by a solid block of text with written without spaces because his spacebar was broken.

In early 2006 Alan Cathcart pulled some strings and earned Confederate an offer to participate in the prestigious Goodwood Festival of Speed in West Sussex, England. Exhibition at the Festival of Speed is by invitation only, so this was an offer that was not to be taken lightly. Case planned to have a Wraith built in time for Cathcart to ride on the Goodwood House grounds; no mean feat considering the event was in July and there had not been a Wraith built since the B91, and the bike would have to be shipped a month in advance to make it to the event on time.

To add to the challenge the only motor available on short notice was a 131 cubic inch (2147 CC) R&R Cycle billet Evolution-clone big twin that was intended for the 2006 F131 Hellcat, which featured completely different architecture compared to the Sportster-based engines used in the prototype Wraiths. With a deadline looming and problems with mounting the big-twin engine into a chassis intended for a Sportster architecture not fully addressed, the Goodwood bike, dubbed B131, was built as a non-running prototype. The machine was completed in June and crated up for shipment to the UK a month in advance of the Festival. Case flew to overseas to setup for the event and await the arrival of the B131.

The machine never arrived. A problem with the customs paperwork meant that the B131 remained in the crate in a holding facility in the USA while Case was getting prepared for the big reveal at Goodwood. The Confederate stand was still put up, featuring exactly zero machines, with labelled plinths sitting empty. It was an embarrassing moment for the company, but one that would be rectified the following year when a Wraith and a G2 Hellcat would successfully complete the transatlantic journey to Goodwood.

Upon his return to Birmingham Case sat down to re-evaluate the big twin Wraith idea and refine the concept. He decided that the Evolution-pattern R&R engine would not work, particularly due to the transmission mount shared with the Hellcat that would preclude using the engine cases as a stressed member within the monocoque structure.

The solution was found in a series of clone motors produced by JIMS USA under license from Harley-Davidson. Based on the Twin Cam architecture introduced by Harley in 1998, the JIMS Beta series twin features a counterbalancing system as found on Twin Cam B series engines used in Softail models from MY2000 onward. Dual counter-rotating balance shafts, placed fore and aft of the crankshaft and driven by a single chain geared off the primary side flywheel, ensured a smooth engine devoid of the usual paint-shaker primary vibration inherent in a massive 45-degree twin. This makes solid mounting possible without having the engine conspiring to rattle the chassis (and the rider) to pieces.

More importantly for the Wraith, the Twin Cam engine featured direct mounting points for the transmission case at the rear of the crankcase, allowing the gearbox to be bolted rigidly to the engine to create a semi-unit structure that could be used as a stressed member. The Evolution series and all prior big twin designs have had completely separate gearboxes that needed to be mounted independently from the engine, precluding the possibility of using the powertrain as a chassis member.

Case designed a proprietary gearbox support that would bolt to the Twin Cam crankcase and house Confederate’s signature vertically stacked five-speed transmission. With this unitized design, the JIMS powertrain was a mere ½ inch longer than a Sportster unit. A "not street legal" (cough) 120 CI 4.125 x 4.5 inch undersquare (approximately 104.8mm x 114mm, 1973 CC) engine was selected, an off-the-shelf counterbalanced JIMS mill intended for use in Softail applications. Aside from a set of Screaming Eagle cams, pushrods, and valve springs, most of the components were produced in-house by JIMS, including the conrods, pistons, tappets, rockers, crankcases and crankshaft. With a 10:1 compression ratio and running premium pump gas, claimed power was 125 HP and 121 LB/FT at the rear wheel (some sources claimed 131 LB/FT - in either case it could probably be deemed adequate).

In a bike that would weigh less than 450 LBS ready to ride, this would be sufficient to give some sparkling performance – without any of the retina-detaching vibration that would normally be expected from a highly-tuned big-inch Harley-clone motor.

The chassis was similar to the previous prototypes, sharing the same hollow carbon-fibre backbone used on the XP1 and the Black Bike – close inspection will reveal that the curve of the spine doesn't quite match the radius of the big twin cylinder heads, as the spine was originally drawn around Sportster dimensions. The suspension contained within the steering neck used on the Black Bike was abandoned in favour of the XP1 multilink girder setup with an external Penske coilover shock mounted in parallel to the steering axis, using a titanium shock spring to reduce steered mass. Rake was 27 degrees, with 4 inches of trail - wheelbase was 58.5 inches.

Another key difference compared to the earlier prototypes was the splitting of the monocoque fuselage into five pieces. The spine and bulkhead panels supported the motor and served as the load-bearing structure, while the belly pan became an unstressed panel that could be unbolted from the rest of the chassis. As before the backbone served as an oil tank for the dry sump motor, while the belly pan contained the fuel cell, exhaust silencer, and battery. An automotive pump was needed to move fuel against gravity from the underslung tank, fed through a regulator to reduce pressure enough to feed a single 51mm Keihin carburettor.

By December 2006 Case had completed a running (but not yet rideable) “B120” Wraith prototype. Plans were made to deliver the bike to Southern California where Alan Cathcart would get some seat time and write a review for Motorcyclist magazine. Case himself would make the trip across the country with several bikes in tow – he would take the opportunity to personally deliver Ryan Reynolds’ now completed Hellcat as well as bring the Wraith to Cathcart.

While the B120 was more or less complete, some detail work remained before Cathcart would be able to ride it. Case took the bike to Eric Schwartzkopf’s Exclusive Customs shop (now DC Custom Designs in Marina Del Rey), then a Beverly Hills-based Confederate partner located just off Santa Monica boulevard. Schwartzkopf had served as an unofficial Confederate service centre and had a favourable relationship with the company, performing repairs, maintenance and warranty work for local owners (read: celebrities), despite the fact that there was no official Confederate dealer or service network at the time.

The Confederate Wraith logo, a stylized W designed by Case so he could paint it on the road with a burnout. Matt Chambers wasn't amused.

Schwartzkopf opened his shop to Case to allow him to finish the B120. With the bike running and a quick shakedown complete, it was hastily delivered to Susan Carpenter from the LA Times for a review. Carpenter discovered a few issues, including a leaking backbone which dripped oil onto the exhaust pipes and rear wheel, and a wonky fuel pump which caused the bike to die on her first ride.

The resulting review was a bit disappointing and it seemed like the test had been unnecessarily rushed, but Carpenter was still charitable to the machine and could not deny the appeal of the Wraith, despite the teething issues and a riding experience that taxed the rider. She noted the smoothness of the counterbalanced engine and the compliance of the unusual front suspension, and the massive amount of attention that riding the Wraith around Los Angeles attracted.

After Carpenter’s ride, Case made some last-minute fixes, such as sealing the leaky oil reservoir in the backbone with Kreem. Before delivering the bike to Cathcart, Case took the opportunity to take the B120 on some shakedown rides around Malibu and the surrounding backroads, including a trip to the famous Rock Store where he encountered Jay Leno (who expressed enthusiasm for the wild design). Case had to deal with an unstoppable amount of interest lavished upon the alien-looking machine on every route and at every stop. As Carpenter had discovered the sight of a Confederate of any sort on the road was cause for investigation, and the awesome-looking Wraith garnered even more attention than usual.

With the major bugs ironed out the B120 was passed to Cathcart. His review noted much improved riding characteristics compared to the Black Bike he had ridden in 2005. He praised the smoothness and power of the JIMS engine, particularly compared to the Revolution Performance powerplant used in the B91. He also noted the good handling, commendable stability (without the need for a steering damper, though production models were fitted with one), and excellent feedback offered by the girder front suspension. Soft springing and controlled damping allowed the bike ride to absorb rough roads without feeling undersprung – it rode comfortably, even if the ergonomics would injure the rider before the suspension harshness ever would.

At this point a retail price of 55,000$ was set for the B120, undercutting the F131 Hellcat which remained the flagship of the line at 67,500$. Chambers claimed that 35 pre-orders were in hand for the Wraith, and that there were plans to build as many as 250 examples with production starting in early 2007. Plans were made for a return to Bonneville in 2007 to prove the mettle of the new Wraith. Case hoped to lead the effort and field his baby on the Salt Flats, just as Nesbitt had done with XP1. However Chambers was pushing Case further away from design and testing and more into production logistics for the company.

A Haas CNC mill and CNC lathe were purchased on Case's recommendation to bring more manufacturing in-house and he was placed in charge of setting up and programming the units - once the machines arrived on site it was clear that a suite of CAM software was needed to convert the company's Solidworks files into real objects, an expensive oversight that angered Chambers. He made Case responsible for getting the critical CNC equipment running, while Ed Jacobs was gradually increasingly billed as Confederate’s star designer. Case was being pulled from the front line and relegated to daily operations, and he began to feel slighted as a result.

Alan Cathcart and Brian Case with the B120 prototype.

Period articles seem to corroborate the shift, with mention of Case’s contributions to the Wraith project steadily disappearing as time went on.* Despite the high-profile nature of the design and the favourable attention the B120 was garnering, it seemed that Chambers preferred to shift focus onto Jacobs’ work, which were more industrial, clean-sheet designs that represented a break from the pre-Katrina machines.

In March 2007 Case was sent to the Daytona Bike Week in Daytona Beach, Florida with two Wraith prototypes. Neale Bayly was invited to ride and review the B120, with Case joining him on the second machine for a friendly blast around the event. Bayly noted some ergonomic issues and clunky clutch and shifting, but was favourable in his assessment. When he rode the newer of the two prototypes he noted some noticeable improvements, what he saw as a sure sign of meaningful progress towards a polished production machine from the tiny company. Retail price was now quoted at 62,500$.

During the fall of 2007 a team consisting of Denis McCarthy, Jason Reddick and Joe Brutton was preparing a B120 for a record attempt at the BUB Speed Trials in September of that year in the Altered – Pushrod Gasoline class (A-PG 2000CC). Case had been helping the crew prepare Bonnie, the Wraith registered as entry 96 in the BUB trials, but was removed from the team by Chambers in August. He was tasked with taking a B120 and a F131 Hellcat to take to Sturgis, North Dakota to participate in the American Motorcycle Dealer World Championship of Custom Bike Building.

The AMD championship is an annual showcase of all that is wild and wonderful in custom motorcycles, with entries from all over the world competing in several categories - but despite their worthiness as entries, Case failed to see how competing in the championship would play into Confederate’s brand image. The AMD championship was a showcase for over-the-top unrideable choppers and candy-coloured styling exercises that represented the sort of ridiculous excess that didn't jive with Confederate's ideology. He felt that the trip was a way of pushing him out of the limelight while his coworkers were working on the Bonneville entry.

The two Confederates were entered in the Production Manufacturer Class, with the requirement that the “entry must be based on a production motorcycle with over 50 units of the model produced annually”; a definition that was probably stretched a bit for the Wraith, which at that point existed only in pre-production form. Regardless of the letter of the rules the two entries swept the class, with the Wraith taking first and the Hellcat second.

The results served as a bit of vindication for Case, but it didn't help his position with Chambers. Upon Case's return to Alabama, the two had a vicious argument. Chambers proceeded to suspend Case from work for two weeks. Frustrated by his increasingly marginalized position within Confederate, Case spent the time off work mulling over his options. He made the decision to leave the company and tendered his resignation upon his return.

With regards to the Wraith, Case felt the design was finished and he had seen it through to production. He felt that he had accomplished what he set out to do, and in so doing had kept his personal promise to Nesbitt (and, to a lesser degree, to Van Halen, who eventually took delivery of a B120 for himself and a Hellcat for his wife).

The Bonneville run went ahead as planned in September, with Bonnie taking to the Flats with Jason Reddick aboard. Featuring a pair of board-tracker style reverse bend handlebars to allow Reddick to tuck in, entry 96 averaged 137.152 mph in the flying mile on their first outing, then 154.778 mph on their second runs. Despite the impressive performance from a naked, air-cooled V-twin powered “production” machine, their trap speeds weren't enough to secure a record in A-PG 2000CC.

The team noted that the bike was running out of gearing at the top end; a subsequent attempt in December 2008 with a revised Wraith, again with Reddick aboard, netted a two-way average of 166.459 mph. With that Confederate earned their first FIM land speed record in the Altered - Pushrod Fuel class (A-PF 2000CC).

Series production of the Wraith was underway by mid-2007, with a retail price that had now inflated to 92,500$. Given the hand-crafted nature of the machines, no two B120s are exactly the same. Some have single front brakes instead of a dual disc setup, some have stainless brake rotors while others have carbon composite, some have BST carbon fibre wheels instead of forged Marchesini items, some have open headers while others route the exhaust through the belly pan. Small detail differences and specification changes abound throughout the production run.

Some complaints were addressed, particularly an extremely heavy clutch pull and clunky shifting, as well as some ergonomic tweaks that made the seating position a bit more bearable (but still far from appropriate for long rides).

Not only are no two Wraiths alike in specification, it would also appear that no two Wraiths ride alike. Each reviewer that had the good fortune to swing a leg over the B120 had a very different opinion of the handling. Most praised the smoothness and power of the JIMS engine, and universally noted the awkward ergonomics, but each noted different characteristics from the girder front suspension. This ranged from the commendable stability and feedback that Cathcart noted in Motorcyclist in 2007 to flighty nervousness that required a maxed-out steering damper described by Mark Hoyer in a 2009 Cycle World review. In a 2008 review for The Telegraph the late Kevin Ash described the steering as vague and slightly unstable until you pushed it hard (which he was reluctant to do on a borrowed machine that retailed for £52,560) and lamented that the multilink front end wasn't tuned for anti-dive properties like a BMW Duolever (Hossack) suspension.

The reason for this variety in handling impressions is unclear. It may have something to do with aberrations in the front girder geometry - either intentional due to tweaking by Confederate over the years, or due to improper suspension setup, or due to minor variations in production. Girder forks tend to have odd dynamic characteristics, with consistent trail for the first few inches of travel followed by a significant change at longer strokes which can lead to odd handling under certain conditions - they work better with very short (and thereby harsh) amounts of suspension travel. The reason is the fork is moving independently of the steering axis of the frame, causing loss of trail under compression when the steering offset changes. This can be tuned to acceptable levels on the street, but is not so great if you plan on racing with a traditional girder - for that you need a Hossack or Fior fork, which links the steering axis to the fork.

Seeing a Wraith in person you are struck by how utterly alien it looks. Like any Confederate it is stupendously well made, with the finest components liberally strewn around a massive motor. The machine is tied together with highest quality CNC milled billet, titanium and matte-finish carbon-fibre. Every fastener and fitting is of the highest quality, if not made specifically for the machine. The carbon-fibre girder blades dominate the aesthetics, but somehow look right. Time has softened the impact of the Wraith's awe-inspiring design, but not by much – these are still amazing looking machines that are unlike anything else on two wheels.

A Wraith is smaller and narrower than you imagined it would be, a 9/10ths scale replica of what you pictured in your head. The weight is carried low and the seat height is barely over 30 inches. While seated on the bike it seems to disappear beneath you. The B120 is slightly larger than the XP1 and B91 but it is still a physically tiny machine that seems like little more than a giant motor with some running gear shrink wrapped around it. You don't realize how compact it really is until you see it in person, sit on it, or witness it in motion with a rider aboard. It is little wonder that the completed B120 weighed in the neighbourhood of 410 LBS dry (some sources claimed 385 LBS), despite packing a near-as-damnit 2000 CC engine with an ungodly amount of torque on tap. The Wraith was billed as Confederate's "sport" machine - considerably lighter and more oriented towards sharp handling than the Hellcat, with a leaned-forward seating position, 120/70-17 and 190/50-17 Pirelli Diablo tires, and a compact chassis. It's hardly a sport bike by any traditional definition but it makes sense when compared to other Confederates.

The proportions of the Wraith look even stranger when a human is perched precariously over it, the minimal saddle disappearing beneath their butts, their legs set back in a semi-rearset position with arms outstretched to meet the flat streetfighter bend of the bars. The ergonomics are, to put it lightly, awkward. Without a fuel tank to grip with your knees the air-cooled engine threatens to alternately roast or shred your legs, with the rear cylinder head and open belt-driven primary drive respectively. You need to keep your knees splayed to keep your jeans intact, and be mindful of the exhaust exit on the right side (if the bike is fitted with open headers) which will likely melt the toe of your boot.

Production continued at a slow rate with steady refinements. Each Confederate is hand assembled by a team of craftsmen, and for most of the company’s history they have only built one machine at a time, with the next order starting only when the current machine is finished and ready for delivery. As a buyer, you put down your deposit and wait your turn for your machine to be built. Each machine is tested for 200 miles by Confederate staff before delivery to the customer; former Confederate engineer Denis McCarthy noted that every ride home was a non-stop barrage of dumbstruck onlookers and 20 minute fuel stops, and he had to build a ramp on his front porch to roll whichever priceless machine he was testing into his home for safekeeping.

After the year of free rent expired at their Fifth Avenue location, the much-touted plan to move Confederate to a larger facility adjoined to the Barber museum quietly fell through. The economic catastrophe in 2008 hit Confederate hard – the ultra-exclusive nature and high prices of their machines killed sales in the wake of a general sobering up of the market. Flash and conspicuous consumption had been building to a crescendo before the downturn, supporting boutique brands and a luxury market that existed in a bubble – in motorcycles as much as in cars, watches, art, boats, booze and anything else that might have graced the pages of the Robb Report.

When that bubble inevitably burst the trend was towards far more discreet displays of wealth and a general shrinking of demand in the luxury market. There were still wealthy clients buying luxury goods, but they now wanted more tasteful, more understated products with solid fundamentals and better resale. Fly-by-night manufacturers of trendy, expensive and flashy goods disappeared, while more established brands like Confederate suffered greatly reduced sales. In 2008 the company produced a mere 37 machines, nowhere near the several hundred units they anticipated before the recession hit. A total of approximately 25 B120s were built, a mere tenth of the originally planned production run.

In Spring 2010 it appeared the Confederate would abandon its operations in Birmingham to return to New Orleans. A 750,000$ loan was offered by the city to entice Confederate to return to Louisiana and develop a lower-priced entry level model (which would ultimately materialize as the sub-50,000$ X132 Hellcat). Opposition from a member of the board of directors created a rift within the company and delayed acceptance of the loan. A lawsuit was taken out against the board member with the accusation that he was attempting to “deadlock” the company.

Meanwhile Confederate’s benefactors in Alabama were not impressed with the about-face after the company had promised tens of millions of dollars in investment and the creation of several hundred local jobs. Ultimately the loan from New Orleans fell through and Confederate remained in Birmingham, moving to their current location on Second Avenue South in 2013.

The B120 evolved into the R135 Wraith Combat, the last hurrah for a platform which had been gradually overshadowed by the introduction of Ed Jacobs’ P120 Fighter in 2009 and third-generation X132 Hellcat in 2010. The R135 was announced in early 2013 as a limited edition of seven examples retailing for 135,000$. The most obvious difference, aside from black anodizing on all the metal surfaces, is the fitting of a JIMS 135 CI 4.3125 x 4.625 inch (110 x 117mm, 2212 CC) Twin Cam engine.

Based on the architecture of the 120 CI mill, the 135 boasted detail improvements across the board, including CNC milled heads, higher lift Screaming Eagle camshafts, and a welded crank pin. JIMS claimed power was up to 136 HP and 135 LB/FT at the wheel with 10.67:1 compression. According to JIMS the 135, like the 120, is a “race only” not-street-legal engine - but no one told Confederate that.

One of Ed Jacobs' Confederate Fighters in for servicing at the Confederate factory. The Fighter succeeded the Wraith as the company's flagship model. It uses a girder front suspension similar to the B120, but with alloy rather than carbon fibre blades.